![]()

Tisha B’Ab - באב תשעה

By Rabbi Dr. Hillel ben David (Greg Killian)

![]()

III. The Day Preceding Tisha B’Ab

IX. When Tisha B’Ab falls on Shabbat

XI. Mashiach and the Final Redemption

XII. The Almond and the Lively Stones

![]()

The three week period between Tammuz 17 and Ab (Ashkenazim say Av) 9 is called Bein HaMetzarim “between the troubles”. In a previous paper we studied the fast of Tammuz 17. Now we are going to jump forward through three weeks of profound trouble to study the fast of the 9th of Ab.

Originally, Yom Teruah was to occur on the seventeenth of Tammuz and Yom Kippurim on the ninth of Av, as the sages assert.[1] Yom Teruah is the day of man’s creation, as we say in the prayers of Yom Teruah, “This day is the beginning of Your works, the remembrance of the First Day,” and the seventeenth of Tammuz was to be the true day of man’s creation. The Creator had formed man to live eternally in the Garden of Eden, but man sinned. On the seventeenth of Tammuz, the Jewish People were to receive the First Tablets.[2]

Tisha B’Ab is the Hebrew name of the fast of the fifth month. Tisha B’Ab is the way “the ninth of Ab” is said in the Hebrew language. Ab is the fifth month of the Biblical year:

|

7. Tishri (Ethanim) |

|

|

2. Iyar (Zif) |

8. Cheshvan |

|

3. Sivan |

9. Kislev |

|

4. Tammuz |

10. Tevet |

|

5. Ab |

11. Shevat |

|

6. Elul |

12. Adar |

The fast of the fifth month is mentioned only obliquely in the Tanach[3]. This fast of the fifth month is mentioned in:

Zechariah 7:1-7 In the fourth year of King Darius, the word of HaShem came to Zechariah on the fourth day of the ninth month, the month of Kislev. The people of Bethel had sent Sharezer and Regem-Melech, together with their men, to entreat HaShem By asking the priests of the house of HaShem Almighty and the prophets, “Should I mourn and fast in the fifth month, as I have done for so many years?” Then the word of HaShem Almighty came to me: “Ask all the people of the land and the priests, ‘When you fasted and mourned in the fifth and seventh months for the past seventy years, was it really for me that you fasted? And when you were eating and drinking, were you not just feasting for yourselves? Are these not the words HaShem proclaimed through the earlier prophets when Jerusalem and its surrounding towns were at rest and prosperous, and the Negev and the western foothills were settled?’“

In the above verse we see the elders inquiring as to whether they are to continue the fast of the fifth month, but, we never see this fast being given in the first place. This is a bit odd. Odder yet is this verse in the Tanach:

Zechariah 8:18-19 Again the word of HaShem Almighty came to me. This is what HaShem Almighty says: “The fasts of the fourth, fifth, seventh and tenth months will become joyful and glad occasions and happy festivals for Judah. Therefore love truth and peace.”

Let’s see how the Talmud views this passage:

Rosh HaShana 18b Why should they not also go forth to report Tammuz and Tebeth seeing that R. Hanah b. Bizna has said in the name of R. Simeon the Saint: ‘What is the meaning of the verse, Thus had said the Lord of Hosts: The fast of the fourth month and the fast of the fifth and the fast of the seventh and the fast of the tenth shall be to the house of Judah joy and gladness? The prophet calls these days both days of fasting and days of joy, signifying that when there is peace they shall be for joy and gladness, but if there is not peace they shall be fast days’! — R. Papa replied: What it means is this: When there is peace they shall be for joy and gladness; if there is persecution, they shall be fast days; if there is no persecution but yet not peace, then those who desire may fast and those who desire need not fast. If that is the case, the ninth of Ab also [should be optional]? — R. Papa replied: The ninth of Ab is in a different category, because several misfortunes happened on it, as a Master has said: On the ninth of Ab the Temple was destroyed both the first time and the second time, and Bethar was captured and the city [Jerusalem] was ploughed.

It has been taught: R. Simeon said: There are four expositions among those given by R. Akiba with which I do not agree. [He said]: ‘The fast of the fourth month‘ — this is the ninth of Tammuz, on which a breach was made in the walls of the city, as it says, On the fourth month on the ninth of the month the famine was sore in the city, so that there was no bread for the people of the land, and a breach was made in the city. Why is it called fourth? As being fourth in the order of months. ‘The fast of the fifth month’: this is the ninth of Ab, on which the House of our God was burnt. Why is it called fifth? as being fifth in the order of months. ‘The fast of the seventh month’: this is the third of Tishri on which Gedaliah the son of Ahikam was killed. Who killed him? Ishmael the son of Nethaniah killed him; and [the fact that a fast was instituted on this day] shows that the death of the righteous is put on a level with the burning of the House of our God. Why is it called the seventh? As being the seventh in the order of months. ‘The fast of the tenth month’: this is the tenth of Tebeth on which the king of Babylon invested Jerusalem, as it says, And the word of the Lord came unto me in the ninth year in the tenth month, in the tenth day of the month, saying, Son of man, write thee the name of the day, even of this selfsame day; this selfsame day the king of Babylon hath invested Jerusalem. Why is it called the tenth? As being the tenth in the order of months. [It might be asked], should not this have been mentioned first? Why then was it mentioned in this place [last]? So as to arrange the months in their proper order. I, however, [continued R. Simeon], do not explain thus. What I say is that ‘the fast of the tenth month, is the fifth of Tebeth on which news came to the Captivity that the city had been smitten, as it says, And it came to pass in the twelfth year of our captivity, in the tenth month, in the fifth day of the month, that one who had escaped out of Jerusalem came to me saying, The city is smitten, and they put the day of the report on the same footing as the day of burning. My view is more probable than his, because I make the first [mentioned by the prophet] first [chronologically] and the last last, whereas he makes the first last and the last first, he, however, following [only] the order of months I [also follow] the order of calamities.

So, we have a fast that is assumed by the Tanach, yet we never see this fast being intiated in the Tanach. This fast was decreed by Chazal, our Sages, as a response to the tragedies that befell us on this day. And HaShem has harkened to their words.

The four fasts mentioned in Zechariah are:

Asarah B’Tevet (Tevet 10 - winter), when the siege of the city of Jerusalem, by the Babylonians, began.

Shiv’ah Asar B’Tammuz (Tammuz 17 - summer), when the walls of the city were breached, several years after the beginning of the siege;

Tisha B’Ab (Ab 9 - summer), when the Beit HaMikdash was destroyed by the Babylonians.

Tzom G’daliah (Tishri 3 - fall) when the Judean governor was assassinated in an Ammonite-generated plot. This brought about the end of Jewish autonomy under the Babylonians.

In Zechariah, HaShem is indicating that these fast days were appropriate and that these days of mourning will be turned into days of joy. The scriptures are strangely quiet on where these fasts began, and on the reasons for these fasts. Never the less, it is obvious that HaShem approves of these fasts of mourning and that some day He will wipe away our tears and turn these days into days of joy. The Nazarean Codicil alludes to this change:

Matityahu (Matthew) 5:4 Blessed [are] they that mourn: for they shall be comforted.

Luqas (Luke) 6:19-21 And the whole multitude sought to touch him: for there went virtue out of him, and healed [them] all. And he lifted up his eyes on his disciples, and said, Blessed [be ye] poor: for yours is the kingdom of God. Blessed [are ye] that hunger now: for ye shall be filled. Blessed [are ye] that weep now: for ye shall laugh.

Yochanan (John) 16:19-20 Now Yeshua knew that they were desirous to ask him, and said unto them, Do ye enquire among yourselves of that I said, A little while, and ye shall not see me: and again, a little while, and ye shall see me? Verily, verily, I say unto you, That ye shall weep and lament, but the world shall rejoice: and ye shall be sorrowful, but your sorrow shall be turned into joy.

When the Beit HaMikdash, The Temple, will be built, physically, the fasts will cease and instead become days of joy. It is likely that Tisha B’Ab will be observed even when the Beit HaMikdash is standing until there is a divine sign of approval, that HaShem once again desires our sacrifices and wants to have His Presence rest in the Beit HaMikdash.

Tisha B’Ab, the 9th of Ab, falls exactly three weeks (21 days) after Shiv’ah ‘Asar B’Tammuz, the 17th of Tammuz and these two dates are always very closely linked in history. The Mishna records the beginning of this period of tragedy:

Ta’anith 26b “Five things befell our fathers on the 17th of Tammuz and five on the 9th of Ab. On the 17th of Tammuz the Tablets [of the Ten Commandments] were broken, and the Daily Whole-offering ceased, and the City was breached, and Apostomus burnt the Torah, and an idol was set up in the Sanctuary.

All five of the tragedies which our Hakhamim date to Shiv’ah ‘Asar B’Tammuz are disruptions of the promise of Sinai, regressions from the intimacy we enjoyed when HaShem first revealed Himself to us. The breaking of the tablets, the burning of the Torah and the construction of an idol in the Sanctuary were clear “rollbacks” from Sinai. The Korban HaTamid and the regular study of Torah (protecting the walls of the city) represents something about Sinai, and these were also suspended or lost on the fateful day of Tammuz 17.

The Mishna then records the end of this period of tragedy:

Mishnah, Taanith 4:6 On the 9th of Ab it was decreed against our fathers that they should not enter into the Land, and the Temple was destroyed the first and the second time, and Beth-Tor was captured and the City was ploughed up. When Ab comes in, gladness must be diminished.”

All five of the tragedies listed which occurred on Tisha B’Ab were rejections or disruptions of the national hope and promise of sovereignty in the land.

Whenever the Tannaim (Hakhamim of the Mishnaic period) present an ordered list (i.e. when they introduce that list with the number of items to appear), it indicates a significance to that number. This does not mean that there is a mystical import (although there may well be), but that if two parallel lists are presented, both with the same number of items and both “ordered”, the symmetry indicates a parallel (or opposing) relationship between the two. The Prophet Yeshayahu puts our two lists together:

Yeshayahu (Isaiah) 2:1-4 The word that Isaiah the son of Amoz saw concerning Judah and Jerusalem. And it shall come to pass in the last days, [that] the mountain of HaShem’s house shall be established in the top of the mountains, and shall be exalted above the hills; and all nations shall flow unto it. And many people shall go and say, Come ye, and let us go up to the mountain of HaShem, to the house of the G-d of Jacob; and he will teach us of his ways, and we will walk in his paths: for out of Zion shall go forth the law, and the word of HaShem from Jerusalem. And he shall judge among the nations, and shall rebuke many people: and they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruninghooks: nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.

What are these things of which the Mishna speaks? The 17th of Tammuz and the 9th of Ab are linked together historically as days on which Israel has been punished for sin.

To discover why Tisha B’Ab was a fast day and a day of mourning; it is necessary to examine, in greater detail, the events that occurred on this date in history.

On Tisha B’Ab, five national calamities occurred:

1. During the time of Moshe, Jews in the desert accepted the slanderous report of the twelve spies, and the decree was issued forbidding them from entering the land of Israel:

Sotah 35a Then all the congregation raised a loud cry, and the people wept that night. Rabbah said in the name of R. Yohanan: That night was Tisha B’Ab; The Holy One, blessed be He, said: They cried for naught, I will establish for them [this night as] a weeping for generations.

2. The First Temple was destroyed by the Babylonian’s fire, led by Nebuchadnezzar. 100,000 Jews were slaughtered and millions more exiled. A year after the Temple was burned, Micah 3:12 was fulfilled, according to the Mishna in Ta’anit 4:6:

Micah 3:12 Therefore shall Zion for your sake be plowed [as] a field, and Jerusalem shall become heaps, and the mountain of the house as the high places of the forest.

Ta’anit 4:6 Five things happened to our forefathers on the 17th of Tamuz and five on the 9th of Ab. On the 17th of Tamuz, the Tablets were broken, the Daily Offerings were stopped, Jerusalem was breached, Apostamos burnt the Torah, and a graven image was placed in the Sanctuary. On the 9th of Ab, our forefathers were sentenced not to enter Eretz Yisrael, the First Beit HaMikdash was destroyed, the Second Beit HaMikdash was destroyed, Betar was captured, and Jerusalem was plowed over

Arachin 11b Come and hear: R. Jose said, Good things are brought about on a good [auspicious] day, and evil ones on a bad one. It is said,

The day on which the first Temple was destroyed was the ninth of Ab,

and it was at the going out of the Sabbath,

and at the end of the seventh [Sabbatical] year.

The [priestly] guard was that of Jehojarib, the priests and Levites were standing on their platform singing the song. What song was it? And He hath brought upon them their iniquity, and will cut them off in their evil. They had no time to complete [the psalm with] ‘The Lord our God will cut them off’, before the enemies came and overwhelmed them. The same happened the second time [the second Sanctuary's destruction]. Now what need was there for song? Would you say that it was on account of the [daily] burnt-offering? But that could not be, for on the seventeenth of Tammuz the continual sacrifice had been abolished. Hence it was on account of a freewill burnt-offering! But how could you think so? Why should an obligatory-offering have been impossible and a freewill-offering available? — That is no difficulty: A young ox may accidentally have come to them!

3. The Romans, led by Titus destroyed the Second Temple. Some two million Jews died, and another one million were exiled, according to the Mishna in Ta’anit 4:6.

In 70 CE the Roman army laid siege to Jerusalem and on the 17th of Tammuz the daily sacrifice was again stopped:

Bamidbar (Numbers) 28:6 [It is] a continual burnt offering, which was ordained in mount Sinai for a sweet savour, a sacrifice made by fire unto HaShem.

Roman centurions on the 9th of Ab burned the Second Temple. The extreme heat of the fire caused gold of the Temple to melt and run in to the cracks and crevices between the stones. When the fire cooled the Roman soldiers used wedges and crowbars to overturn every stone in their search for the gold.

There are twenty-two letters in the Hebrew alphabet. There are twenty-two days from the 17th of Tammuz up to and including the 9th of Av. Throughout history, these have been days of destruction in the Jewish calendar. These are the days when the stones of the buildings are taken apart. Mystically, we should understand the destruction of the Temple as the destruction of the body of Mashiach, composed of all Israel. When we (Israel) bring disunity to the body of Mashiach it is manifested in the destruction of the Temple which represents Mashiach’s body.

One year later on the 9th of Ab the Romans plowed the Temple mount and the city of Jerusalem to prepare the area to be turned into a Roman colony.

Micah 3:12 “Therefore, because of you, Zion will be plowed like a field, Jerusalem will become a heap of rubble, and the Temple hill, a mound overgrown with thickets.”

Mashiach alludes to the destruction of the Temple and its subsequent rebuilding in three (days) thousand years:

Marqos (Mark) 14:58 We heard him say, I will destroy this temple that is made with hands, and within three days I will build another made without hands.

Matityahu (Matthew) 17:23 And they shall kill him, and the third day he shall be raised again…

Yochanan (John 2:18-22) Then answered the Jews and said unto him, What sign shewest thou unto us, seeing that thou doest these things? Yeshua answered and said unto them, Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up. Then said the Jews, Forty and six years was this temple in building, and wilt thou rear it up in three days? But he spake of the temple of his body. When therefore he was risen from the dead, his disciples remembered that he had said this unto them; and they believed the scripture, and the word which Yeshua had said.

4. The Bar Kochba revolt was crushed by Roman Emperor Hadrian. The city of Betar, the Jews’ last stand against the Romans, was captured and liquidated. Over 100,000 Jews were slaughtered, according to the Mishna in Ta’anit 4:6.

5. The Roman general Turnus Rufus plowed under the Temple area and its surroundings. Jerusalem was rebuilt as a pagan city, renamed Aelia Capitolina, and access was forbidden to Jews, according to the Mishna in Ta’anit 4:6.

This section was excerpted and edited from a work of Rav Yitzchak Etshalom.[4]

Whenever the Tannaim (Rabbis of the Mishnaic period) present an ordered list (i.e. when they introduce that list with the number of items to appear), especially in non-Halakhic literature, it indicates a signficance to that number. This does not mean that there is a mystical import (although there may well be), but that if two parallel lists are presented, both with the same number of items and both "ordered", the symmetry indicates a parallel (or opposing) relationship between the two.

The placement of these two "themes" and their lists of tragedies in juxtaposition implies a continuum from one to the other. This sequenced relationship is more clearly evidenced by the tradition that we have to regard the time period between Shiv'ah 'Asar b'Tammuz and Tish'ah b'Av as a unit, marked by customs of mourning.[5]

From this Mishnah (and our analysis & comments), we can infer four points:

a) Each of these days has a "theme".

b) This "theme" explains the inclusion of all five items on each list.

c) There is a parallel relationship between the two. (It is not an "opposing" relationship as the two sets are not presented as antitheses, rather they are all of one type - tragedy).

d) There is a continuum between the two "themes".

|

Rejection of the Sinai Connection |

Tammuz 17 |

Rejection of Tzion |

Tisha B’Ab |

|

Sinai was a Chuppah. We were unfaithful under the chuppah. |

The "Luchot," the tablets upon which the Ten Commandments were engraved, were broken by Moshe. |

They cried for naught, I will establish for them [this night as] a weeping for generations.[6]

In other words, the wailing was the event that shaped the nature of Tish'ah b'Av. Just as we found in regards to Shiv'ah 'Asar b'Tammuz, the tragedies of Tish'ah b'Av are rooted in our desert sojourn.

Indeed, their eager acceptance of the scouts' negative report was tantamount to a rejection of the "pleasant land", the Land which HaShem had promised them, flowing with milk and honey and all manners of blessing. |

Our forefathers were sentenced not to enter the land of Israel because of the spies. |

|

Bamidbar (Numbers) 28:6 It is a continual burnt-offering, which was offered in mount Sinai, for a sweet savour, an offering made by fire unto HaShem.

The daily Tamid was to be a reminder and recovenanting of the B'rit Sinai - the covenant of Sinai. |

The Korban Tamid, the continual daily sacrifice, was discontinued. |

The destruction of the Batei Mikdash and the rejection of the Land are of a type - they both belong to the de-evolution of a different mission from that established at Sinai.

|

The First Temple was destroyed by the Babylonian’s. |

|

The protection of the city comes not from its military might, rather from its scribes, teachers and students of Torah. A breach in the protection of Torah. every time that we engage in Torah study, we are effectively reenacting the Sinai experience.[7]

The study of Torah (saying the Shema) parallels the Korban haTamid - it is an ongoing Mitzvah which has two time-foci: Morning and evening. The lapse of study which allowed the breach of the city walls is of a type with the suspension of the Korban haTamid - the cessation of the "day-and-night" worship of HaShem, originated at Sinai. |

The wall around the city of Jerusalem was breached. |

The destruction of the Batei Mikdash and the rejection of the Land are of a type - they both belong to the de-evolution of a different mission from that established at Sinai.

We can now understand why the destruction of the two Batei Mikdash belongs with the rejection of the Land. One common interpretation of the behavior of the scouts and the reaction of the people, was that they did not want to enter the Land because they knew that that would spell the end of their intimate relationship with HaShem. They would become a nation among nations - with the responsibility of ethical leadership among them. The destruction of the Batei Mikdash - ideally the world-wide center for HaShem's instruction through the Jewish people (keep in mind that the Sanhedrin was seated right in the Beit haMikdash in the "office of hewn stone") - meant the (temporary) suspension of the opportunity to completely fulfill this responsibility. The fall of Beitar and the plowing of the city were, again, seemingly fatal blows to our national destiny and opportunity. |

The Second Temple was destroyed. |

|

That great gift which we received in the desert, among protective flames, now went up in flames.

This is a clear "regression" from Sinai. That great gift which we received in the desert, among protective flames, now went up in flames. This is a clear disruption of the Sinaitic experience. |

Apostamus burnt the Torah scroll. |

Bar-Kokhba ("son of the star" - held Messianic hopes for the people. We lost sovereignty over Eretz Israel.

Roughly seventy years after the destruction of the second Temple, the great rebellion led by Bar-Kokhba ("son of the star" - later renamed "Bar Koziba" - the "son of deceit") held Messianic hopes for the people. Even the great R. Akiva considered Bar Kokhba to be the Mashiach and carried his weapons.[8] Not only was the timing of the rebellion possibly inspired by the model of the Babylonian exile, in which there were only seventy years during which the Temple Mount lay fallow - but it was chiefly the attempt to regain Jewish sovereignty over our Land. The crushing of this hope was certainly similar to the decree against our ancestors, denying them entrance into - and sovereignty over - the Land. |

Betar was captured. |

|

It was not just the establishment of an idol that was the tragedy - it was the placement of this idol in the Sanctuary - just like the abomination of the golden calf was its placement at the foot of Sinai in the wake of the Revelation. |

An idolatrous image was placed in the Beit HaMikdash, the Holy Temple. |

This "final" tragedy was certainly of a type with the sentence against our ancestors. Keeping in mind that Yerushalayim is not only a spiritual center, it is also our political capitol, the plowing under of the city represented the final blow to our hopes for sovereignty in the Land. |

The Roman general Turnus Rufus plowed under the Temple area and its surroundings. |

|

All five of the tragedies which the Rabbis date to Shiv'ah 'Asar b'Tammuz are disruptions of the promise of Sinai - regressions from the intimacy we enjoyed when HaShem first revealed Himself to us. The breaking of the tablets, the burning of the Torah and the construction of an idol in the Sanctuary were clear "rollbacks" from Sinai. The Korban haTamid and the regular study of Torah (protecting the walls of the city) represents something about Sinai - and these were also suspended or lost on the fateful day of Shiv'ah 'Asar b'Tammuz. |

All five of the tragedies listed which occured on Tish'ah b'Av were rejections or disruptions of B'rit Tziyyon - the national hope and promise of sovereignty in the Land. |

||

|

First, we were to fulfill B'rit Sinai, maintaining and constantly strenghtening our exclusive relationship with HaShem - and we are also to fulfill B'rit Tzion, using that special relationship to teach and inspire the world. This is the tragedy of these three weeks - our failure in both regards, one leading to the next. It is not for naught that the traditions of our people have created a sense of continuity between these two fast days - they are, indeed, a sequence which we must reverse, through the introspection and Teshuvah motivated by a fast.[9]

The role of the Beit haMikdash as an international focus is not only found in the prophecy regarding HaShem's instruction; it will ultimately be a prayer-center for the entire world: "...For my house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples."[10]

May this be the last year when these fasts remain days of sadness: "Thus says HaShem of hosts: The fast of the fourth month (Tammuz), and the fast of the fifth (Av), and the fast of the seventh (Tishri), and the fast of the tenth (Tevet), shall be seasons of joy and gladness, and cheerful festivals for the house of Yehudah: therefore love truth and peace." |

|||

Several other calamitous events took place on Tisha B’Ab:

1. Esau confronted Jacob, on his return to Canaan. Genesis 33:1ff. Rashal Bereshit Vayish quoted in Seder HaDorot. This event in Jacob’s life is a prophecy for his descendants. This confrontation speaks of the ultimate confrontation in the end of days.

2. Pope Urban II declared the First Crusade. Tens of thousands of Jews were killed, and many Jewish communities obliterated.

3. In 1290 King Edward I ordered the expulsion of all Jews from England on the 9th of Ab. (And they did not regain the right to settle there again until 1657.)

4. The Spanish Inquisition culminated with the expulsion of Jews from Spain on Tisha B’Ab in 1492. This is the same date on which Christopher Columbus (himself a Jew) set sail.

5. World War One broke out on Tisha B’Ab in 1914 when Russia declared war on Germany. German resentment from the war set the stage for the Holocaust.

6. On Tisha B’Ab, deportation began of Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto.

7. The Gulf war started on the 9th of Ab, when Saddam Hussein went to war against Kuwait and in the months that followed proceeded to hurl his 39 missiles at Israel.

As a side note: The only observed collision between a planet and another solar body began on Tisha B’Ab, a Sabbath. Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 began slamming into the surface of the planet Jupiter, known in Hebrew as Zedek, the righteous one. This event may have connections to the other Tisha B’Ab events. On July 17 (Tisha B’Ab) 1994, the planet Jupiter was struck by 21 fragments of a comet. The comet (Shoemaker-Levy 9) collided with this planet... likely fulfilling Luke 21:26, where Yeshua says that, prior to his return the “heavenly bodies would be shaken.” Is all this coincidence? I don’t think so. Jupiter was the high-god of Rome, it was the one whose temple replaced HaShem’s house in Jerusalem and whose name (Capitolina) adorned the city for centuries. Jupiter (also known as Marduk to Babylonians) was the high god of Zoroastrianism, the religion of Nebudchenezzar (who had the first Temple burned in 586b c). See the connection? HaShem had symbolic “revenge” on Rome -and- Babylon through Jupiter (high god of both empires), when the planet was pummeled on this fitting anniversary in 1994 (5754 A.M.).

So, why do we fast on the 9th? Before the Gemara addresses this question, it mentions the opinion of Hakham Yochanan on this topic:

Taanit 29a R’ Yochanan said that “If I had been present at the time when the Sages established the day as a fast, I would have established the 10th of Ab as the day of the fast, as that was the day the Temple burnt for the most part.”

The Sages disagreed and felt that the fast should be on the ninth. The Gemara explains that the opinion of the Sages was that it was better to fix the commemoration according to the beginning of the calamity (the 9th of Ab, when the Temple was first set on fire), rather than according to the day on which the unfolding of the calamity itself occurred for the most part.

The fast of the 9th of Ab is a “hard” fast in terms of importance and in severity of restrictions. It is second only to the fast of Yom HaKippurim.

Since these tragedies occurred on Tisha B’Ab, the Sages decreed this day as a fast day. The restrictions on the 9th of Ab are more severe than the other fast days ordained by the Sages.

According to Jewish tradition, the ninth day of the fifth Jewish month is the saddest day on the Biblical calendar. This day of solemn reflection and fasting has been observed since the destruction of Solomon’s temple. It is still observed today.

Why did so many tragedies befall us on the same date?

The Talmud reveals to us the answer to this question:

Ta’anit 29a “Reward is saved for a day of merit, and destruction is saved for a day of guilt”

According to the Mishna. Because our forefathers committed such a terrible sin on the ninth of Ab in the days of Moshe, the day became one reserved for destruction. Every year, when that day comes around, the original sin of our forefathers is brought back to light. Since we have not yet fully corrected their misdeeds, HaShem may not extend to us His usual lovingkindness on that day, leaving us vulnerable to impending adversity. The ninth of Ab has thus become a “weak link” in the chain of Jewish history.

The Sages of the Talmud, in Sanhedrin 90a, tell us that whenever HaShem punishes someone it is always done in such a way that the punishment corresponds to the sin that was committed (Middah kneged Middah, “Measure for measure”). One classic example of this is the punishment of the Egyptians who enslaved the Bnai Israel. The Egyptians persecuted the Israelites through water, by drowning Jewish babies in the Nile river[11], and their ultimate punishment was that they themselves were drowned in the Red Sea.[12]

As we have pointed out, the catastrophic events of the ninth of Ab were all precipitated by the original sin of Moshe’s generation. Here, too, it can be shown that the specific events that transpired on these days were all clearly wrought with the theme of “Middah Keneged Middah”, measure for measure.

Let us first consider what the Tisha B’Ab sin of our ancestors was. The Jews sent spies to scout out the Land of Israel prior to entering in. The spies brought a bad report, and the people believed the bad report. Instead of trusting in HaShem and His appointed leaders, the people rallied rebelliously behind the sinful spies.

Bamidbar (Numbers) 14:1 “The people wept all through that night”.

This sin, the Mishna tells us, took place on Tisha B’Ab. “That night that the people wept was Tisha B’Ab eve. HaShem said to them, `You wept on this day for no good reason; I will establish this day as a day of weeping for all generations’“[13]. The tragedies that befell the Jews throughout the generations were apparently further punishments for the original sinful act committed by the generation of the Exodus.

The Torah tells us that the punishment meted out immediately to those who allied themselves with the spies was that they would have to wander about in the desert for forty years:

Bamidbar (Numbers) 14:34 “one year for each day” of the spies’ excursion.

The Torah makes it clear that the punishment of forty years in the desert was “measure for measure”, forty for forty. Can we say the same of the latter-day punishments, the four tragedies listed in the Mishna in Ta’anit? A closer examination reveals that in fact we may.

The sin of the Bnai Yisrael was that they rejected the Land of Israel. They were willing to pass up possession of the Promised Land, not even trying to conquer it, although HaShem had already told them of its unique virtues.

The fall of the Temples that took place centuries later was more than just a loss of the opportunity to perform the sacrificial rite ordained by the Torah. It was the event that, symbolically and actually, spelled the end of organized Jewish settlement in Israel. The destruction of the Temple and the concept of exile are always considered to be two sides of the same coin by our Sages[14]. The Torah itself seems to make this connection in:

Vayikra (Leviticus) 26:31-2 “I will destroy your Temple... and will scatter you among the nations.”

It is clear that the punishment of the destruction of the Temple, which is tantamount to exile of the population, has a very close correlation with the original sin of Tisha B’Ab. Because the Bnei Israel expressed on Tisha B’Ab an unwillingness to accept the gift of the Land of Israel, they eventually lost the Land of Israel on that same date.

Betar was the central stronghold of the Bar Kochba rebellion against Rome[15]. Some sixty years after the destruction of the second Temple the Jews, led by the charismatic and courageous Bar Kochba, tried to throw off the Roman yoke from their necks. They even succeeded to some degree in establishing an autonomous Jewish state in Israel for several years (132-135 CE). When the Bar Kochba uprising was finally put down by the Romans with the fall of Betar, it effectively represented the end of any Jewish hope to sovereignty in the land of Israel for the foreseeable future. This too, then, is clearly an appropriate punishment for the original sin of the spies and their rejection of the Land of Israel.

The last of the five events of Tisha B’Ab can be interpreted along the same lines. The final razing of Jerusalem was designed to quash any hopes among the Jews for a restoration of their sovereignty, or even of their ability to dwell, in the city.

This section was adapted from:

“Hitna’ari Me-afar Kumi” –

The Secret of Jewish Regeneration

by Rav Yair Kahn

Apart from the mitzva to pray every day, there is a special commandment to pray in times of national calamity. According to the Rambam in the beginning of Hilkhot Ta’aniyot, the verse:

Bamidbar (Numbers) 10:9 “And if war should come upon your land, the enemy who troubles you, you shall blow on the trumpets“

Is not a commandment simply to blow the trumpets, but rather includes prayer and petition. Even the Ramban, who rules (in opposition to the Rambam) that daily prayer is only a Rabbinic commandment, admits at least partially that there is a Torah commandment to pray in times of calamity. He declares, “And if perhaps they interpret prayer as a biblically-derived principle... then this is a mitzva for times of calamity...”[16].

The foundation for the obligation to cry out to HaShem in times of calamity is the obligation of teshuva. And so the Rambam continues, “And this is part of teshuva...” There is a special obligation of teshuva in times of calamity, as it is written:

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 4:30 “When you are in distress and all these things befall you... you shall return to HaShem your God”

The Rambam explains, “At a time when calamity strikes and they cry out and they blow on the trumpets, all will know that calamity has come upon them because of their evil deeds... and this is what will cause the calamity to be lifted from upon them. But if they do not cry out and do not blow [trumpets] but rather say, ‘This has happened to us since this is the way of the world, and this calamity is coincidental,’ this is the way of gross insensitivity, and will cause them to hold fast to their evil deeds, and other calamities will be added. This is what the Torah means when it says, ‘And if you walk crookedly (in Hebrew: “keri,” from the root of the word meaning “coincidence”) with Me then I will likewise walk crookedly with you’ - in other words, I shall bring calamity upon you in order that you return. If you maintain that your calamities are coincidental then I will increase those ‘coincidental’ calamities.”

The biblical obligation of prayer and teshuva, repentance, at a time of calamity is extended by Chazal to obligate fasting: “And the Hakhamim instructed that there should be fasting for every calamity, which comes upon the community, until Divine mercy is achieved”[17]. And what stands at the center of these obligations is the Divine Providence, which watches over Knesset Yisrael and entreats them, calling: “Shuvu banim shovavim, Return, O backsliding children!” Obviously, the very obligation to pray and fast at a time of calamity is based on the assumption that by means of sincere and genuine teshuva the calamity will be removed.

As opposed to “calamity” (tzara) an “evil decree” (gezera) cannot be removed. It expresses not Divine Providence but rather the distancing of the Divine Presence and HaShem “hiding His face,” as it were. “Hakham Elazar said: Since the day on which the Temple was destroyed, there is a wall of iron that stands between Israel and their Father in Heaven“[18]. The reaction to an evil decree is not prayer but rather mourning and surrender to HaShem’s inscrutable will. “And Hakham Elazar said: Since the day on which the Temple was destroyed, the gates of prayer are locked”[19].

The seventeenth of Tammuz, despite the five tragic events, which took place on this day, is defined as a day of calamity. It is true that on this date the first set of tablets were shattered, but following prayer on the part of Moshe Rabbeinu and teshuva on the part of the nation, we merited to receive a second set of tablets. Likewise, on this date the walls of Jerusalem were indeed breached, the enemies stood ready to enter, and, therefore, it was a time of calamity for the Jewish nation. But it was only on Tisha B’Ab that a tragic decree was issued: “On Tisha B’Ab it was decreed upon our forefathers that they would not enter the land,” and despite Moshe’s entreaties, the attempts to mitigate the sharpness of the decree reached its tragic conclusion at Chorma[20].

On the other fasts there is a special obligation of prayer and entreaties. The selichot and Torah portions read on these fasts, focus on Moshe Rabbeinu’s prayer following the sin of the golden calf, the declaration of the Thirteen Attributes of Mercy. On the other hand, on Tisha B’Ab, the day established for weeping for all generations, we sit on the floor, read Eikha, Lamentations, and recite lamentations, and the Torah reading and haftara on this day speak of the destruction. This distinction between Tisha B’Ab and the other fasts was already formulated by Rabbenu David[21]: “On Tisha B’Ab there is no ‘Ne’ila’ prayer, nor are twenty-four blessings recited, because [this day] is set aside not for prayer but rather for mourning.”[22] Likewise, on Tisha B’Ab the “titkabel” clause is not included in the recitation of Kaddish[23], and the sheliach tzibbur, the prayer leader, does not recite “Aneinu” in his repetition of the Amida of Shacharit[24]. Rav Soloveitchik, zt”l, explained that only on the other fasts does one fulfill the special obligation of prayer at a time of calamity, as explained above. But on Tisha B’Ab, “Even though I cry out and call for help, He has blocked my prayer”[25]. Thus, even though Tisha B’Ab has the status of a fast day, it is still entirely different in its nature and purpose from any other public fast.

In terms of the other prohibitions of the day, Tisha B’Ab is again different from the other fasts. On one hand, there are prohibitions, which are similar to those of Yom HaKippurim[26]. On the other hand, these prohibitions reflect the mourning of Tisha B’Ab, rather than the positive obligations of prayer and teshuva. The Gemara[27] states, “The Hakhamim taught, all the laws pertaining to mourning apply on Tisha B’Ab as well; a person is forbidden to eat and drink[28], to anoint his body, to wear leather shoes and to engage in sexual intercourse...”[29]

In light of the above, let us return to the sugya in Rosh Hashana: “Tisha B’Ab is different since on this day many sorrows befell us.” According to the fundamental distinction which we have drawn between a calamity and a decree, we can explain that what we are referring to here is not a quantitative addition of calamities on Tisha B’Ab over and above those of any other fast. We are dealing not with a calamity but rather with a decree. Therefore, we do not fast within the framework of the obligations of prayer and teshuva in order that the calamity will pass, but rather as part of our expression of sorrow and mourning over the bitter decree.

On other fast days, aside from Yom HaKippurim and Tisha B’Ab, some poskim hold that pregnant and nursing women are not required to fast. Other poskim, however, hold that the minhag is that they should fast, unless they find it difficult. A person who is ill or suffering is not required to fast, even if there is no fear of danger to health.

On Yom HaKippurim and Tisha B’Ab, however, pregnant and nursing women are required to fast the entire day even if they are suffering, with this difference: On Yom HaKippurim a person is required to fast even if he is ill, unless there is danger to life. On Tisha B’Ab, if a person is suffering greatly or is old or weak and may become ill, even if there is no danger to life, he / she should not fast. A person with only a headache or similar minor discomforts, however, is required to fast.

If a nursing woman’s fasting will harm the infant (e.g., the infant is ill and a physician says that the fast will adversely affects the infant, the milk will be adequate for the child and the child refuses to eat or nurse from others), she may eat or drink as required. Where there is any question, a Hakham should be consulted.

If a person is not required to fast because it is dangerous, he is prohibited from fasting.

Even those persons who are not required to fast on Tisha B’Ab should not indulge or eat more than is necessary to preserve their health.

Boys under Bar Mitzva, even those twelve years of age and girls under Bat Mitzva, even those under eleven years old, are not required to fast the entire day as they are required on Yom HaKippurim. According to Hakham D. Eider, noted halachic scholar, there are various opinions among Poskim as to whether children should fast part of the day.

When a circumcision, or a Pidyon Haben (redemption of a firstborn son), is celebrated on the day preceding Tisha B’Ab, and if meat is being served, the feast should be held in the forenoon.

One should not walk for pleasure on the day before the 9th of Ab; and it is customary to study in the afternoon only the subjects permitted on Tisha B’Ab. Many poskim hold that although on Tisha B’Ab itself one is limited in what he may learn, on Erev Tisha B’Ab, however, one may learn all portions and topics of Torah. This is how many poskim conducted themselves, even when Erev Tisha B’Ab occurred on a weekday and certainly when it was on Shabbat.

Concerning fasting on erev Tisha B’Ab, if a person fasts every Monday and Thursday, and erev Tisha B’Ab occurs on a Monday, or if one observes a yartzeit on erev Tisha B’Ab (many fast on a yartzeit) or if he would want to fast because of a disturbing dream, a Rav should be consulted to resolve the need for fasting two consecutive days. One who observes yartzeit on the day before Tisha B’Ab should resolve on the first occasion not to fast any longer than until noon; then he should say the Mincha gedolah (the big Mincha), that is at 12:30 p.m., partake of a meal, and afterwards, at the approach of evening, eat the concluding meal.

There are many laws regarding the last meal before the fast. The proper minhag is to eat the regular meal before the Mincha service. Afterward, we pray Mincha, omitting the Tachanun (petition for Grace), because Tisha B’Ab is called a holiday, as it is written:

Eicha (Lamentations) 1:15 “He has called a holiday for me.”

As Tisha B’Av Approaches

At the approach of evening, we should sit on the ground, or a low stool, but it is not necessary to remove the shoes. Three should not sit down to eat together, in order that they should not be obliged to recite the Grace in company. Only bread and a cold hard-boiled egg should be eaten at this meal, and a morsel of bread should be dipped in ashes and eaten. One should finish this meal while it is yet day.

All that is forbidden to be done on Tisha B’Ab is also forbidden in the twilight. One should, therefore, remove the shoes before twilight.

During the afternoon prior to Tisha B’Ab, it is customary to eat a full meal in preparation for the fast.

At the end of the afternoon, we eat the “Seudah Hamaf-seket”, a meal consisting only of bread, water, and a hard-boiled egg.

The egg has two symbols: The round shape reminds us of a sign of the cycle of life. Also, the egg is the only food which gets harder the more it is cooked, a symbol of the Jewish people’s ability to withstand persecution.

Food eaten at the “Seudah Hamaf-seket” is dipped in ashes, symbolic of mourning. The meal should preferably be eaten alone, while seated on the ground in mourner’s fashion.

For Sefardim, the final meal before the fast (if it is eaten after the middle of the day) may not consist of more than one cooked food. However, if it is usual to cook two foods together, such as rice and lentils (Kitchri), they are considered as one and are permitted.

The basic prohibitions of the day are:

1. Eating,

2. Drinking,

3. Washing,

4. Cohabitation,

5. Wearing leather shoes,

6. Learning Torah (with exceptions), and

7. Anointing with oil - once the practice of Kings.

We will explore these in more depth in the following sections.

Bathing for pleasure is forbidden, whether in hot or cold water; it is even forbidden to put one’s finger in water. In any case, there is no question that it is permitted for health and ritual purposes, when not for pleasure’s sake. Hence, we may wash our hands in the morning, but we must be careful not to wash more than the fingers, for this is what constitutes the ritual morning ablution, as an evil spirit rests on the fingers in the morning. After having dried the hands slightly, and while they are still moist, we may pass them over our eyes. One whose eyes are filmy after awakening from sleep, and who is accustomed to wash them every morning, is permitted to wash them as usual, and he need have no scruples about it. Likewise, if one’s hands are soiled, he may wash the soiled spots. After responding to the call of nature, we may slightly wash our hands, as we are accustomed to do. We should also wash our fingers for the Mincha services.

One who is accustomed to rinse his mouth or teeth daily may do so even with water on the other fast days, if the bad taste in his mouth causes him distress. On Tisha B’Ab, however, this is permissible only in instances of great distress. However, as care must be taken not to swallow the water, he should bend over when rinsing. Prohibited on Yom HaKippurim, rinsing one’s mouth with mouthwash or brushing one’s teeth without water, on Tisha B’Ab is questionable.

Women are allowed to rinse the edibles to be used for cooking, inasmuch as the purpose is not to wash the hands. One who is on his way to perform a precept, and he’s unable to proceed unless he crosses a stream, may cross it on his way there and on returning, and he need have no scruples about it. However, if he’s going for his own gain, he may cross on his way there, but not on returning. One, who returns from the road, and his feet are sore, may bathe them in water.

Although only bathing for pleasure is forbidden, nonetheless, a woman whose time for taking the ritual immersion occurs on the night of the Ninth of Ab, should not perform the immersion as cohabitation is taboo on Tisha B’Ab. A woman, however, may wash the parts of the body that must be washed before beginning her seven clean Days.

One may soak a cloth in water on Erev Tisha B’Ab and after it has dried to a point where it is not sufficiently damp to wet something else substantially, he may wipe his face, hands and feet. This is permissible even if the intention is for pleasure. Since it is considered dry, according to halacha, it is not considered washing.

A bride within thirty days after her wedding may wash her face.

Wearing shoes is forbidden if they are made of leather; but wearing shoes made of cloth, or the like, if they are not trimmed with leather, is permissible. Those who have to walk among non-Jews may wear shoes, so, as not to expose themselves to ridicule; but one should place some earth in the shoes. However, a righteous person should rightly cling to the rule. Men who stay in stores are surely forbidden to wear shoes, One who has to walk a long distance, since walking barefoot would cause him great distress, is permitted to wear shoes, but he must remove them in approaching a city. But one who rides in a vehicle is forbidden to wear shoes.

Wearing leather shoes for medical reasons is permissible. Therefore, one may wear leather shoes if his foot was injured and sneakers or other permissible shoes would not afford adequate support. Where there is any doubt, consult a Hakham.

One is permitted to learn Torah selections relevant to tragic events and destruction. The general principle is to devote one’s thoughts to mourning tragic events, rather than diverting oneself with other matters.

We are forbidden to greet a neighbor on the 9th Day of Ab, even to say “Good morning,” or the like. If greeted by an ignorant person or by a non-Jew, we should return the greeting feebly; otherwise we might incur their anger. We are likewise forbidden to send a gift to a neighbor, because this is a form of greeting. This is the practice of mourners.

Anointing, too, is forbidden for pleasure; and if one has scabs on the head, or if it is necessary for some other remedy, it is permissible.

Swallowing capsules, bitter medicine tablets or bitter liquid medicine is permissible.

We should not walk in the marketplace or in a busy shopping area, for there we might be prompted to indulge in laughter and merriment. Some authorities forbid the smoking of tobacco the whole day, while others permit it in the afternoon in the privacy of one’s own home.

With regard to work, our custom is to forbid even unskilled labor the night of Tisha B’Ab and up to noontime, if it takes time to do it. But work that does not take long to do, like the lighting of candles, or tying something up, is permitted. In the afternoon, all work is permitted. It is also the custom to forbid the transaction of business in the forenoon, but to permit it in the afternoon. However, a G-d-fearing man should not do any work nor transact any business the whole day, so that his mind is not diverted from mourning. A non-Jew may do all manner of working, and if this work is of a nature that if done at once might cause a loss, one is permitted to do it himself. A non-Jew should do the milking of cows, but when that is impossible, one may milk them himself.

One who engages in business or work where it is prohibited will not see a blessing from this forbidden work. One who eats or drinks on Tisha B’Ab will not be among those privileged to participate in rejoicing over Jerusalem. Experiencing its rejoicing will reward whoever mourns properly over Jerusalem.

We do not engage in business or other distracting labors, unless it will result in a substantial loss.[31]

It is customary not to sit on a bench or a chair, either at night or in the day till noon, sitting only on the floor. In the afternoon this is permissible, All the other things that are forbidden in Tisha B’Ab may not be done until the stars come out.

In the morning, the tefillin are not put on, because they are called an “ornament.” Neither is the big tallit put on, because it is written[32]: “Bitza imrato,” and the Targum translates it: “He rent His royal garment”; but the small tallit should be put on, without saying the benediction thereon.

It is the custom not to start to prepare the meal before noon on Tisha B’Ab, but it is permissible if it is to be a religious feast.

If there is an infant to be circumcised, the circumcision should be performed when the recital of “Kinnot” is concluded. The father and the mother of the infant, the sandek and the mohel are permitted to don their Sabbath attire in honor of the circumcision. After the circumcision, they should remove these garments. Candles may be lit in honor of the circumcision, and the goblet of wine should be given to a minor to drink.

Cohabitation is forbidden, and one should be careful not even to touch his wife. It is proper not to have sexual intercourse on the night of the 10th of Ab day, unless it is on the night of the ritual immersion, or if one is about to go on a journey, or has returned from a journey.

A man should deprive himself of some comfort when he goes to sleep on the night of the 9th of Ab. If he is accustomed, for instance, to sleep on two pillows, he should sleep on only one. Some people sleep on the floor during the night of Tisha B’Ab, and place a stone underneath the head, to conform to what is written about Jacob:

Bereshit (Genesis) 28:11 “and he took from the stones of the place,”

Because, the Hakhamim say, he foresaw the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple, and he said (verse 7): “How fearful,” etc. All these depend on the character of the individual.

From the onset of the month of Ab joyfulness should be lessened, and one who has a court-case with a non-Jew should postpone it till after the tenth of Ab.

Negotiations for and acquisitions of items for joyous purposes, such as marriages, are postponed till after the Ninth of Ab. However, they are permitted if the items would not be available later, or if they would then be more costly.

While some Sepharadim do not perform weddings from Rosh Hodesh to the Ninth of Ab, the accepted practice is to be strict and forbid it from Tammuz 17.

The week of Tisha B’Ab is calculated from the Shabbat preceding it to Tisha B’Ab. During this week, cutting of hair is prohibited, and this is the Minhagh of most Sepharadim. Ashkenazim prohibit it for the twenty-two days. Some Sepharadim have adopted this custom also.

We do not take haircuts or wash our clothes or bodies until midday of the 10th of Ab.

Sepharadim do not partake of meat and wine from the night after Rosh Chodesh Ab. But on Rosh Chodesh itself, meat and wine are consumed in honor of the special day[33]. Ashkenazim abstain from Rosh Chodesh. It is common among Sepharadim to break the fast of Tisha B’Ab with a chicken meal. The Ashkenazi custom, however is to postpone this till the day of the tenth of Ab. One should not sit on the floor itself, while eating this meal, as this is not good according to kabbalah. Instead, one should sit on a mat or something similar.

One may not cut one’s nails during this week, though on ‘Ereb (the eve of) Shabbat Chazon it is permitted. However, if the nails extend beyond the flesh of the fingers they may be cut, even on this week, as it is a great obligation to do so according to the kabbala.

Eicha, Lamentations, is read at night and again in the morning, in accordance with the Sepharadim. Some Ashkenazim, however, read it only at night.

1. Lights in the synagogue are dimmed, candles are lit, and the curtain is removed from the Ark. The chazzan leads the prayers in a low, mournful voice. This reminds us of the Shekinah which departed from the Holy Temple.

2. The Book of Eicha (Lamentations), Jeremiah’s poetic lament over the destruction of Jerusalem and the First Temple, is read both at night and during the day.

3. Following both the night and day service, special “Kinot” (elegies) are recited.

4. In the morning, the Torah portion of Devarim[34] is read, containing the prophecy regarding Israel’s future iniquity and exile. This is followed by the Haftorah from Yiremiyahu (Jeremiah) 8:13, 9:1-23, describing the desolation of Zion.

Sefardim

Evening Service:

Reading of the Book of Lamentations

Morning Service:

Torah Reading:

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 4:25-40

Haftarah:

Yirmeyahu (Jeremiah) 8:13 – 9:23

Book of Iyov (Job)

Reader 1 – Devarim 4:25-29

Reader 2 – Devarim 4:30-34

Reader 3 – Devarim 4:35-40

Yirmeyahu 8:13 – 9:23

(In Sephardi Congregations this Haftarah is read in Ladino)

Book of Iyov (Job) is read

Afternoon Service:

Torah Reading:

Shemot (Exodus) 32:11-14; 34:1-10

Haftarah:

Hoshea (Hosea 14:2-10 (AV: 14:1-9)

Mikha (Micah) 7:18-20

Reader 1 – Shemot 32:11-14

Reader 2 – Shemot 34:1-3

Reader 3 – Shemot 34:4-10

Hoshea 14:2-10

Mikha 7:18-20

5. In the afternoon, Shemot (Exodus) 32:11-14 is read. This is followed by the Haftorah from Yeshiyahu (Isaiah) 55-56.

6. Since Tallit and Tefillin represent glory and decoration, they are not worn at Shacharit. Rather, they are worn at Mincha, as certain mourning restrictions are lifted.

7. Birkat Kohanim is said only at Mincha, not at Shacharit.

8. Prayers for comforting Zion and “Aneinu” are inserted into the Amidah prayer at mincha. The prayer of Nacheim (“Console...”) is recited in the mincha Shemoneh Esreh on Tisha B’Ab because mincha is the time the birth of Mashiach, whose name is Menachem.

9. Before the fast is broken, it is customary to say Kiddush Lavanah because on Tisha B’Ab Mashiach will be “born”. [In the blessing we say, “And they will seek David their king.”]

10. We skip parts of the Uva L’tzion and kaddish. We skip those parts where we ask HaShem to forgive us.

11. We don’t say Tachanun as we do on all other fast days.

Now that we have explored the prayers of Tisha B’Ab, we should have noticed something VERY VERY unusual. We should have noticed that there were no selichot, no neilah, and no other prayers for forgiveness! On this tragic day we do not repent because on this day our prayers will not be heard.

On Tisha B’Ab HaShem will not hear our prayers for forgiveness!

We read about this unusual response in the reading of Eichah:

Eichah (Lamentations) 3:8 Also when I cry and shout, he shutteth out my prayer.

Eichah (Lamentations) 3:44 Thou hast covered thyself with a cloud, that [our] prayer should not pass through.

Perhaps the most poignant of all is the command of HaShem to Yeremyahu NOT to pray for the people:

Yeremyahu (Jeremiah) 11:14 Therefore pray not thou for this people, neither lift up a cry or prayer for them: for I will not hear [them] in the time that they cry unto me for their trouble.

On this day there is no teshuva, no repentance. Even teshuva is forbidden in mourning! If we arrive at Tisha B’Ab with our teshuva, we have arrived unprepared. We have contributed to the destruction of the Beit HaMikdash, the Temple. It is our duty to build ourselves into the lively stones as a fit place for the Shechina to rest.

We must do teshuva before Tisha B’Ab! We must repent while there is yet time!

When Tisha B’Ab falls on Shabbat, the following special conditions apply:

1. The fast is pushed off until Saturday night and Sunday.

2. All other prohibitions of Tisha B’Ab (washing, learning Torah, leather shoes, etc.) are permitted on Shabbat itself, except for marital relations.

3. Care should be taken to complete “Seudah Shlishit” before sundown.

4. “Seudah Hamaf-seket” may include meat and wine.

5. Arbit on Saturday night is delayed, so that everyone can say “Baruch Hamavdil bein kodesh li’chol,” then remove their leather shoes and come to Shul.

6. Havdallah on Saturday night is recited only over a candle, without wine or spices. On Sunday night, Havdallah is then said over wine.

According to the Rashba, Shabbat the ninth of Ab is not a day of mourning, no prohibitions apply to Shabbat, and it is reasonable to conclude that Sunday the tenth is the proper day of the fast and no leniency’s should apply.

According to the Shulchan Aruch, Sunday is not in principle the proper day of mourning; hence, a father of a brit milah does not complete the fast.

This section is an extract from the Encyclopedia Judaica.

The mourning rites of Tisha B’Ab are reflected in the following changes in the synagogue liturgy and usage:

1 The lights in the synagogue are dimmed and only a few candles are lit, as a symbol of the darkness which has befallen Israel. In some rites (Sephardi, Yemenite), it is customary to extinguish all lights immediately after the conclusion of the evening service prior to the reading of the Kinot (“dirges”), and the oldest member of the congregation or the hazzan then announces: “This year is the... so and so... since the destruction of the Holy Temple.” Afterward he addresses the congregation with words of chastisement and repentance in the spirit of the saying: “Each generation in which the Temple is not rebuilt should regard itself as responsible for its destruction.” This is answered by wailing and crying. Then the lights are lit again.

2 The curtain of the Ark is removed in memory of the curtain in the Holy of Holies in the Temple which, according to the Talmud, was stabbed and desecrated by Titus. In some Sephardi synagogues where the Ark normally has no curtain, a black curtain is hung and the Torah Scrolls themselves are draped in black mantles.

3 The congregants sit on low benches, footstools, or on the floor as mourners do during the shivah period.

4 The Chazzan recites the prayers in a monotonous and melancholy tune.

5 Some people change their customary seats in the synagogue.

6 In some congregations the Torah Scroll is placed on the floor and ashes put on it while the congregants recite the words: Eicha (Lamentations) 5:16 “the crown is fallen from our head” or other appropriate verses[35].

7 The prayer service is the regular weekday service, with the following changes: In the evening, the Scroll of Eicha (Lamentations) is followed by special dirges, Kinot. In the Sephardi rite the Song of Moses, Deuteronomy 32, is substituted for the Song of Moses, Shemot (Exodus) 15, which is normally recited after the morning Psalms. After the main part of the morning service Kinot are recited commemorating many of the tragic events in Jewish history (in the Sephardi rite they are recited before the Reading of the Torah). In the Ashkenazi rite these include Sha’ali Serufah be-Esh by R. Meir of Rothenburg (occasioned by the burning of the Talmud in Paris in 1242), Arzei ha-Levanon (commemorating the death of the “Ten Martyrs”), the Odes to Zion, beginning with the famous Ziyyon ha-lo Tishali of Judah Halevi and concluding with Eli Ziyyon ve-Areha sung to a special melody (see Eli Ziyyon). The Sephardi Kinot differ from the Ashkenazi and do not include those mentioned. There is, however, one which is based upon the Four Questions of the Passover Seder, the opening stanza of which is: “I will ask some questions of the holy congregation; How is this night different from other nights? Why on Passover eve do we eat matza and bitter herbs, while this night all is bitterness...?”

8 During the reader’s repetition of the Amidah the Anenu prayer is inserted between the seventh and eighth benedictions as on all fast days. In the silent Amidah it is recited in the 16th benediction of the afternoon service and in the Sephardi and Yemenite rites at all services. The Italian rite recites it in the morning and afternoon services. In the afternoon service a special prayer Nahem is added to the benediction for the restoration of Jerusalem.

9 From the Middle Ages it became customary except among certain oriental communities not to wear tallit and tefillin during the morning service. (They are considered to be ornaments, and the tefillin in particular are held to be Israel’s “crown of glory.”) They are worn instead during the afternoon service. (Thus the blessing “who crowns Israel with glory” is omitted from the morning benedictions, because it refers to the tefillin.)

10 The morning service as well as the afternoon service include readings from the Torah. In the morning the reading is Devarim (Deuteronomy) 4:24–40, and the haftarah Yiremiyahu (Jeremiah) 8:13–9:23; in the afternoon service Shemot (Exodus) 32:11–14 and 34:1–10, and, as haftarah, Yeshiyahu (Isaiah) 55:6; 56:8 as on all fast days. The Sephardi haftarah is Hosea 14:2–9. In some rituals the person called up to the Torah says: “Blessed be the righteous Judge”, the verse by which mourners are greeted.

11 Some people sprinkle ashes on their head as a symbol of mourning. In Jerusalem it is customary to visit the Western Wall on Tisha B’Ab, where Lamentations and the Kinot are recited by the different communities according to their rites. There are many other local mourning customs. Visits to the cemeteries, especially to the graves of martyrs and pious men, were frequent, in order to implore the deceased to intercede for the speedy redemption of Israel. School children used to throw seed-burrs of plants at each other in Poland and in Russia. The shofar was blown in Algiers in memory of the ancient fast day ceremonies in the time of the Temple. Women anointed themselves with fragrant oils and perfumes on the afternoon of Tisha B’Ab, for they believed that the Mashiach would be born (or appear) on this day and it would become a great holiday (Egypt). In the evening after the fast, some people greet each other with the formula: “You shall soon enjoy the comfort of Zion.”

Chazal[36] say that the Mashiach will be “born” on the Ninth of Av, and that in the days after Mashiach comes, the Ninth of Av will be a holiday of joy, as it was originally intended. This is reflected in the laws of the day, as we don’t say Tachanun. It is not like the other fast days:

Midrash Rabbah - Lamentations I:51 The following story supports what R. Judan said in the name of R. Aibu: It happened that a man was ploughing, when one of his oxen lowed. An Arab passed by and asked, ‘What are you?’ He answered, ‘I am a Jew.’ He said to him, ‘Unharness your ox and untie your plough’ [as a mark of mourning]. ‘ Why? ‘ he asked. ‘ Because the Temple of the Jews is destroyed.’ He inquired, ‘From where do you know this?’ He answered, ‘I know it from the lowing of your ox.’ While he was conversing with him, the ox lowed again. The Arab said to him, ‘Harness your ox and tie up your plough, because the deliverer of the Jews is born.’ ‘What is his name?’ he asked; and he answered, ‘His name is “Comforter”.’ ‘What is his father’s name?’ He answered, ‘ Hezekiah.’ ‘ Where do they live? ‘ He answered, ‘In Birath ‘Arba in Bethlehem of Judah.’

The Hakhamim of the Talmud teach that on the afternoon of Tisha B’Ab, the very day of the destruction, Mashiach is “born”. This suggests that each year, on Tisha B’Ab, the seeds of redemption are planted. This day, each year, has the energy to bring forth the Mashiach and the final redemption!

The meaning of Mashiach’s birthday [being on Tisha B’Ab] is not that he came into this world on that date, because if so, he could not in actuality be described as the “Redeemer of the Jewish people” then; it means that Mashiach, as an adult, is revealed as the “Redeemer of the Jewish people,” (comparable to birth in the literal sense when a newborn is revealed into this world), and that he is prepared and worthy to redeem the Jewish people in actuality. From all the indications given by our Sages, we are in the “generation of the footsteps of Mashiach,” and the Geulah, the redemption, can come at moment’s notice, so Mashiach has to be prepared to take us out of galut, exile.

Every Jew has within him a spark of Mashiach, which empowers and vitalizes him, and with this spark every Jew can transcend the limitations of nature and revert to a super-natural order. As we are at the end of this final galut, when we have already completed the the work of refinement in galut, with all the trials and tribulations, the “birthpangs of Mashiach,” the terrible, horrific unimaginable things which have transpired in our generation [“may they never happen again”] – it is very plain and simple that now is the time when Jews are about to go into Eretz Yisrael in the final redemption with Mashiach Tzidkeinu.

Mashiach is waiting impatiently for the moment when he will redeem the Jewish people from galut, and this can come immediately: considering the achievements of the Divine service during all this time, it is certain that Mashiach is coming “today.” Having already definitely done teshuvah, we have the promise and the ruling that the Geulah must come immediately, it will not be delayed even as much as a wink of an eye, especially since it is also a situation of merited and deserving, so that Mashiach will come “on the clouds of heaven.” The practical lesson for us from all of this: We have to know that the time of Mashiach’s arrival is certainly here; we have but to “stand prepared” to greet him with longing and yearning for Mashiach. and this will certainly bring about his revelation. In an auspicious time when his “mazal“ is predominant, this trickles down to every Jew, that he should add in “a single mitzva” which will tip the scales for the individual and the entire world, and bring salvation and the true, complete redemption immediately. [37]

* * *

“Hakham Abin opened as follows: ‘Feed me bitterness’, on the eve of Pesach, ‘fill me with gall’, on Tisha B’Ab[38]. The bitter herbs of the first night of Pesach are related to the pain of Tisha B’Ab. The two events are always the same day of the week.”[39]

The above passage again connects the idea of redemption to Tisha B’Ab. In the same way that Pesach and its seder speak of the final redemption, so too, does this day speak of our final redemption. The two days are linked for our redemption.

A birthday is a time when the specific mazal, constellation, or spiritual energy as manifest by the mazal, which was in force during a person’s birth is once again ascendent, giving him power and strength. Thus, the birthday of Mashiach is a time when he, and the redemption with which he is associated, are granted new power. This power, in turn, hastens the advent of the day when the redemption will become actually manifest.[40]

* * *

The following is an excerpt from Reflections & Introspections, Elul – Rosh Hashanah – Yom Kippur – Sukkos, TORAH INSIGHTS OF HAGAON HAGADOL RavMoshe Shapiro.

“The Sages state (Yalkut Shimoni chapter 782), “In each month of the summer months, the Holy Blessed One wished to give to Israel a festival. In Nisan He gave to them Passover, in Iyar He gave to them Passover Minor,” which we call Pesach Sheni, “and in Sivan He gave to them Shavuot. In Tammuz, He had in mind to give to them a great festival, but they made the Golden Calf, and it cancelled Tammuz, Av, and Elul. Tishri came, and it recompensed them with Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, and Succoth. The Holy Blessed One said of it, “Shall it recompense others and not take its own? Give it its day: “On the eighth day, it shall be Atzeret for you” (Bamidbar 29:35).”

“The implication is that the great festival of the Seventeenth of Tammuz was to be Rosh Hashanah, but due to what occurred, it became the fast of the Seventeenth of Tammuz. The great festival of the Ninth of Av was to be Yom Kippur, but again, due to what occurred, it became the bitter and evil day of destruction. At the beginning of Elul was to be the Festival of Succoth, and it would conclude the festivals of summer. The festival of Tishri itself was to be what we currently call Shemini Atzeret; this festival belongs to Tishri inherently.”

“In fact, Shemini Atzeret, the Atzeres of Succoth was to arrive just as Shavuot, the Atzeret of Passover. There, we count forty-nine days from the day after the first of Passover, and the fiftieth day is Shavuot. Here, we were to count forty-nine days from the day after the first of Succoth, meaning from the second day of Elul. This ends on Hoshana Rabbah, and the fiftieth day is Shemini Atzeret.”

“The sages ask this in actuality.[41] Why do we not have the same custom regarding the Atzeret of Succoth as we have regarding the Atzeret of Passover? Why do we not count fifty days from Succoth and then celebrate the Atzeret of Succoth?”

“They answer that the Creator did not wish to overburden the Jewish People to come to Jerusalem for the pilgrimage during the rainy season. Fifty days from the current date of Succoth would occur in the middle of the winter, and it is not conducive for travel.”

“Clearly, it is befitting for there to be a counting of forty-nine days and then to celebrate the Atzeret of Succoth. Thus, if Succoth were in Elul that is how it would be.”

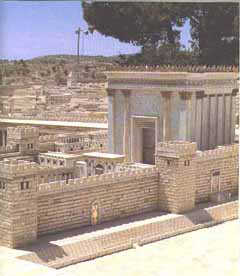

Almond Tree in bloom

The Gemara[42] asserts that a hen’s egg generally takes twenty-one days to hatch, just as the almond blossom takes twenty-one days to develop into a fruit. Tosefot ad. loc. quotes a Midrash[43] that explains a prophesy of Yirmiyahu based on this:

Yirmiyahu (Jeremiah) 1:1-16 Moreover the word of HaShem came unto me, saying, Jeremiah, what seest thou? And I said, I see a rod of an almond tree. Then said HaShem unto me, Thou hast well seen: for I will hasten my word to perform it. And the word of HaShem came unto me the second time, saying, What seest thou? And I said, I see a seething pot; and the face thereof [is] toward the north. Then HaShem said unto me, Out of the north an evil shall break forth upon all the inhabitants of the land. For, lo, I will call all the families of the kingdoms of the north, saith HaShem; and they shall come, and they shall set every one his throne at the entering of the gates of Jerusalem, and against all the walls thereof round about, and against all the cities of Judah. And I will utter my judgments against them touching all their wickedness, who have forsaken me, and have burned incense unto other gods, and worshipped the works of their own hands.

Yirmiyahu was shown an almond branch in a prophetic vision of retribution. The point of his vision, then, was to demonstrate that just as the almond blossom takes twenty-one days to produce fruit, so too, the destruction of Jerusalem will be accomplished during a twenty-one day period; from Shiv’ah Asar B’Tammuz, the 17th of Tammuz, until Tisha B’Ab, the 9th of Ab.

The almond can be regarded as having two periods of ripening. It is edible together with its rind a few weeks after the tree blooms, while the fruit is still green. Its second ripening is three months later, when the outer rind has shriveled and the inside cover has become a hard shell[44].

In its exposition of Jeremiah’s vision, the Talmud has the first ripening in mind: “Just as twenty-one days elapse from the time the almond sends forth its blossom until the fruit ripens, so twenty-one days passed from the time the city was breached until the Temple was destroyed”[45], the twenty-one days being the period between the Seventeenth of Tammuz and the Ninth of Ab.

Beth-El was originally called Luz[46] which is the less common word for almond or almond tree in Hebrew, but loz is the regular Arabic word for almond.

The Place of the world, the Beit HaMikdash, The Temple, is a place of connection, a place of intimacy. This place was called Bethel which means “The House of God”. This was THE PLACE of the world. This was the place where Jacob slept for the first time in fourteen years:

Bereshit (Genesis) 28:10-22 Jacob left Beersheba and set out for Haran. When he reached a certain place, he stopped for the night because the sun had set. Taking one of the stones there, he put it under his head and lay down to sleep. He had a dream in which he saw a stairway resting on the earth, with its top reaching to heaven, and the angels of God were ascending and descending on it. There above it stood HaShem, and he said: “I am HaShem, the God of your father Abraham and the God of Isaac. I will give you and your descendants the land on which you are lying. Your descendants will be like the dust of the earth, and you will spread out to the west and to the east, to the north and to the south. All peoples on earth will be blessed through you and your offspring. I am with you and will watch over you wherever you go, and I will bring you back to this land. I will not leave you until I have done what I have promised you.” When Jacob awoke from his sleep, he thought, “Surely HaShem is in this place, and I was not aware of it.” He was afraid and said, “How awesome is this place! This is none other than the house of God; this is the gate of heaven.” Early the next morning Jacob took the stone he had placed under his head and set it up as a pillar and poured oil on top of it. He called that place Bethel, though the city used to be called Luz. Then Jacob made a vow, saying, “If God will be with me and will watch over me on this journey I am taking and will give me food to eat and clothes to wear So that I return safely to my father’s house, then HaShem will be my God And this stone that I have set up as a pillar will be God’s house, and of all that you give me I will give you a tenth.”

This “certain place” is defined by Strong’s as:

4725 maqowm, maw-kome’; or maqom, maw-kome’; also (fem.) meqowmah, mek-o-mah’; or meqomah, mek-o-mah’; from 6965; prop. a standing, i.e. a spot; but used widely of a locality (gen. or spec.); also (fig.) of a condition (of body or mind):-country, X home, X open, place, room, space, X whither [-soever].

The Midrash calls this “certain place”, “The Place”: